13.A model of mistrust ------Charlemagne

*Not for the first time Belgium is a microcosm of the EU. And not in a good way

THE last time Belgium held a general election, in 2007, it took 282 days to form a fully fledged coalition government. The country is now being called to fresh elections on June 13th. Forming the next coalition may well be harder.

Among the Dutch-speakers of Flanders in the country’s north, the polls are topped by Bart De Wever, a populist bruiser who describes French-speakers in the south as “dependents” addicted to transfers from the thrifty Flemish. He wants to split the tax system in two, as well as the welfare state and most other public spending. The king and the country called Belgium can stay, for the time being, but Flanders’s “natural evolution”, says Mr De Wever, is to become an independent state.

Among the French-speakers who make up 40% of Belgium’s population, polls show a lead for Elio Di Rupo, a Socialist whose battle cry is “solidarity” within Belgium (ie, continued transfers from Flanders). Though Belgium’s public debt stands at 99% of national income, Mr Di Rupo promises above-inflation spending rises on health and pensions. In a final flourish, he is calling for price controls on 200 staples, such as bread and milk. Somehow, a coalition must be formed with the consent of these two men.

It has not been an impressive election campaign. Belgium’s leaders have barely addressed Europe’s most dangerous economic crisis in a generation. Instead they have argued about language rights in a set of Flemish communes with lots of French-speaking residents, and other local arcana.

For years, federal Belgium thought it would be a model for the European Union, in which powers would flow down to regions and up to a Euro-superstate, leaving nations as empty shells in the middle. Unsurprisingly, Belgians loved this vision: it promised to dissolve their troublesome kingdom into a United States of Europe (with Brussels as its capital). But Europe went another way. Nation states proved hard to kill off and a few big national leaders dominate EU politics.

Instead, this election has revealed Belgium as another sort of model for Europe: a union in which north-south divisions undermine economic and political integration. Consider Mr De Wever’s sloganeering. He does not just sound off about transfers of billions of euros from Flanders. He also charges that tax inspectors are less zealous in the south of the country. He grumbles that the motorways of Flanders are lined with radar traps, whereas Wallonia’s are camera-free. The Flemish regional budget minister, a party colleague, complains that frugal Flanders plans to run a surplus by 2011, whereas the French-speaking rulers in Brussels and Wallonia plan to let their deficits run for another five years. A health spokesman for the N-VA, Mr De Wever’s party, talks of profiteering, bill-padding and “francophone abuses” in southern hospitals.

Just to Belgium’s north, Europe barely featured in the Dutch election on June 9th. But Mark Rutte, leader of the right-wing liberal VVD and probable next prime minister, vowed to seek big cuts in Dutch payments to the EU and dismissed EU aid for poor regions as mostly “money recycling”. These are the complaints of a north-south culture clash, just as clearly as headlines in Germany asking why Germans should pay for Greeks to retire at 55.

Discipline is what they need

This has consequences for the EU. Europe is divided between a Germanic block determined to save the euro with budgetary discipline and a southern block, led by France, that wants to save the day with things like cheaper borrowing through Eurobonds and transfers from rich to poor in a “fiscal union”.

Yet if Belgium, a single country with a single treasury, is struggling to preserve its transfer union, what hope does Europe have of creating one from scratch? Southern advocates of “solidarity” accuse northerners of selfishness. That is simplistic: this is not just a fight about money. Belgium offers Europe a further lesson: for voters to consent to transfers of wealth, they must feel that the recipients are democratically accountable to them.

Belgium is dying as a nation for several reasons, but a big one is its lack of national democracy. Belgian political parties divided along French- and Dutch-speaking lines four decades ago, and most voting districts are split the same way. Southerners who believe in Belgium cannot vote against Mr De Wever. Voters in Flanders worried about deficits can do nothing to sanction free-spending Mr Di Rupo. This democratic deficit is reproduced at the European level. Germany has been criticised for proposing punitive governance in the euro zone that could see rule-breaking countries lose EU funds or voting rights. To hear some in Brussels, Germany is at best obsessed with monetary stability, at worst a selfish bully. But Germany’s focus on discipline is arguably an attempt to fix a democratic deficit. Germans may have to bail out Greece or Spain without any power to choose a Greek or Spanish government committed to reform. The next best thing might be binding rules that force southern governments to take seriously those things dear to German voters.

Euro-dreamers say a fiscal-transfer union could be built on the legitimacy of the European Parliament. In the real world, most voters neither know nor care who represents them in the EU’s parliament. Build too weighty a project on those fragile foundations and it will crumble. Well then, say the dreamers, at future European elections, presidents of the European Commission and some members of the European Parliament should stand in pan-European constituencies. Once the continent embraces pan-European politics, all manner of budgetary and fiscal unions would become possible. It all sounds logical enough, but Europe’s democratic divisions run deep. Just ask Belgium, a country of 10m people struggling to achieve pan-Belgian politics.

12.Obama v BP -------American politics and business

*America’s justifiable fury with BP is degenerating into a broader attack on business

FOR over a month, Barack Obama watched the oil spill spread over the Gulf of Mexico with the same powerless horror as other Americans. Finally, lampooned by his countrymen for his impotence, he was spurred into action. He attacked the only available target-BP-and, to underline the seriousness with which he takes this problem, he gave his first Oval Office address on the subject.

The address got poor reviews; the attack on BP better ones. This week the firm bowed to pressure, and announced that it was, in effect, handing over $20 billion to the government to pay for compensation and clean-up, as well as cancelling the payment of any dividends this year and setting up a fund-of a mere $100m-to compensate unemployed oil workers.

This may do Mr Obama some good. Whether it will benefit America is more doubtful. Businessmen are already gloomy, depressed by the economy and nervous of their president’s attitude towards them. This episode will not encourage them.

Booted and spurred

There is good reason for Americans to be furious with BP. The authorities reckon that the oil may be flowing at a rate of 60,000 barrels a day-far more than the company estimated, and the equivalent of an Exxon Valdez every four days. Efforts to stem the toxic plume have met with only modest success (see briefing).

A permanent solution may be available in August, but only if the drilling of relief wells to intercept and plug the stricken one goes according to plan.

BP already had a miserable safety record in America. In 2005 an explosion at one of its refineries in Texas killed 15 people. In 2006 corrosion in its pipelines led to a sizeable spill on Alaska’s North Slope. Since then, regulators have often fined it for breaking safety standards. There are indications that BP’s approach to the drilling of the Macondo well was similarly slapdash. Engineering measures that might have prevented the calamity were not carried out, tests of safety equipment delayed. The firm’s emergency-response plan spoke of protecting the area’s walruses-an easy task, since there aren’t any-and consulting an ecologist who had died in 2005.

America has a well-developed system for getting companies to pay for the damage they do; and BP long ago accepted that it would pay in full. But that was never going to satisfy the country’s corporate bloodlust. An outfit called Seize BP has organised demonstrations in favour of the expropriation of BP’s assets in 50 cities. Over 600,000 people have supported a boycott of the firm on Facebook. Several of BP’s gas (petrol) stations have been vandalised.

The politicians, eager as ever to stay in tune with the nation, joined in. Ken Salazar, the secretary of the interior, vowed to keep the government’s boot on BP’s neck. At one of the many recent hearings at which BP executives have been hauled over the coals, a Republican congressman suggested that the chairman of BP’s American arm should commit ritual suicide. Mr Obama said he was looking for arses to kick.

After the macho rhetoric came the demands for cash. Mr Obama decided to “inform” BP that it must put adequate funds to meet all compensation claims into an escrow account beyond its control, although he has no authority to do so. Nancy Pelosi, the speaker of the House of Representatives, instructed it not to pay a dividend until all claims tied to the spill are settled. Her fellow Democrats in Congress are trying to raise BP’s liability retroactively-the sort of move America’s courts rightly frown on. Mr Salazar, on even thinner legal ice, suggested that the government would hold BP accountable not just for the harm directly done by the spill, but also for the jobs lost in the oil business thanks to the freeze on oil drilling in deep water that he himself has imposed.

Investors seem to be worried that the wrath of American officialdom will ruin BP. They have driven down its value by $89 billion since the well erupted, far in excess of all but the most dire forecasts of the ultimate costs of the spill. Corporate America, normally quick to resist government intrusion, has kept strangely silent, as though businessmen are afraid of the consequences of sticking their heads above the parapet.

The attack on BP seems to have paid off for the administration, in that the firm has caved in to most of its demands. Mr Obama’s swipes at the company have lent him an unfamiliar air of forcefulness. And, as everybody in Washington knows, so long as BP meets its commitments, government attempts to meddle in the firm’s management, much less seize its assets, will be rejected by the courts. So why not keep going?

Vladimir Obama

For several reasons. The vitriol has a xenophobic edge: witness the venomous references to “British Petroleum”, a name BP dropped in 1998 (just as well that it dispensed with the name Anglo-Iranian Oil Company even longer ago). Vilifying BP also gets in the way of identifying other culprits, one of which is the government. BP operates in one of the most regulated industries on earth with some of the most perverse rules, subsidies and incentives. Shoddy oversight clearly contributed to the spill, and an energy policy which reduced the demand for oil would do more to avert future environmental horrors than fierce retribution.

Mr Obama is not the socialist the right claims he is (see article). He went out of his way, meeting BP executives on June 16th, to insist that he has no interest in undermining the company’s financial stability. But his reaction is cementing business leaders’ impression that he is indifferent to their concerns. If he sees any impropriety in politicians ordering executives about, upstaging the courts and threatening confiscation, he has not said so. The collapse in BP’s share price suggests that he has convinced the markets that he is an American version of Vladimir Putin, willing to harry firms into doing his bidding.

Nobody should underestimate the scale of BP’s mistake, nor the damage that it has caused. But if the president does not stand up for due process, he will frighten investors across the board. The damage to America’s environment is bad enough. The president risks damaging its economy too.

11.The 70-30 nation------- Lexington

*America’s faith in free enterprise seems impervious to setbacks. That has not stopped the angst on the right

THE past couple of years have not been private enterprise’s finest hour. From the collapse of Lehman Brothers to the implosion of General Motors and Chrysler to BP’s oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, one great firm after another that had boasted of making society richer has turned into an expensive liability for taxpayers at best or, at worst, a menace to the general prosperity or the environment. You might expect this sequence of calamities to have made people sourer towards capitalism and friendlier to the state. But in America, at least, you would be wrong. Americans remain deeply wedded to the free-enterprise system.

Even after the collapse of Wall Street and all that has followed, an overwhelming majority of Americans say in opinion polls that they prefer capitalism to socialism. Gallup found in January that 61% had a positive view of capitalism and about the same percentage had a negative view of socialism. In March last year the Pew Research Centre asked Americans whether they were better off in a free-market economy “even though there may be severe ups and downs from time to time”. Seventy percent answered in the affirmative. Most Americans also say their federal income taxes are too high. Even those who favour higher taxes on the rich think the top rate should be 20% or less.

If Americans will stand behind the free-enterprise system come what may, it makes sense for Barack Obama’s opponents to portray the president as a danger to it. “We are facing a ruthless secular-socialist machine that is alien to America’s history and traditions,” bellows Newt Gingrich, the hero of the Republican victory of 1994, as he flogs his latest book (“To Save America”). The Republicans are sure to do well in November’s mid-terms.

And yet Arthur Brooks, the president of the American Enterprise Institute, thinks defenders of capitalism need to do more. They need, even in America, to remake the moral case for it.

Mr Brooks considers entrepreneurship central to American culture, maybe literally a part of its DNA (thanks to all of those immigrants importing the gene that makes you get up and go). His guess is that the country is divided about 70% to 30% in favour of free enterprise. But he poses an intriguing question. If that is true, how did a politician with as “little regard for free enterprise” as Mr Obama become president in the first place? The answer in his own book (“The Battle”) is that although America is a 70-30 nation in favour of free enterprise, the 30% are firmly in charge.

How could that possibly be? Mr Brooks offers two explanations. The first is that the 30% coalition is led by people with undue influence: rich intellectuals, Hollywood types, media folk and university teachers. Also in the mix that elected Mr Obama are blacks and Hispanics, who trust government more than white Americans do. Second, for all America’s faith in capitalism, the economic calamity of 2008 helped the minority fool the majority into thinking that the crisis was caused by the private sector and that the state knew how to solve it. In Mr Brooks’s opinion it was the other way round: the state’s social engineering (in particular, government support for dodgy mortgages) caused the crisis, and its “remedies” will only make matters worse.

To save capitalism in the years to come Mr Brooks wants to persuade Americans all over again that a free-enterprise system is not only more efficient than socialism but morally superior as well. He has an elegant theory about this. Neither state-engineered equality of income, nor money itself, makes people as happy as their own “earned success in life”, which people are much freer to earn in a system of free enterprise. But both Mr Brooks’s subtle approach and Mr Gingrich’s unsubtle one suffer from a shared weakness. Where in fact is the evidence that Mr Obama is even remotely a “socialist”?

To stand up this straw man the president’s critics recycle the same small crop of incriminating quotations time and again. Mr Obama told Samuel “Joe the Plumber” Wurzelbacher on the campaign trail in 2008 that “when you spread the wealth around, it’s good for everybody.” Gotcha! In recent speeches to graduating students he has counselled against materialism and extolled the virtues of public service. More evidence! “That strikes me as exactly the wrong message to send to young people,” huffs Mitch Daniels, the governor of Indiana and a Republican presidential might-wannabe. Please. Platitudes like these have been the stuff of commencement speeches from time immemorial.

There is no master plan

Government has expanded on Mr Obama’s watch. His administration is spending $1 trillion on economic stimulus, has propped up two of the big three car firms instead of letting them implode and introduced a far-reaching reform of health care. Whatever you think of the merits of the first two decisions it takes a peculiar mixture of amnesia and paranoia to see them as a master plan to turn America socialist, rather than as a series of ad hoc responses to the exigencies of the crisis Mr Obama inherited. As for the third, it is a funny socialism that gives private, for-profit insurance firms the main responsibility for delivering health care.

The American right misses Mr Obama’s real flaw. He is not a “socialist”; but he does not understand business. As even Democrat-leaning CEOs complain, he neither expresses enough appreciation of capitalism nor shares the wavelength of those who practise it. Bosses are ushered in for photo-calls and then ignored. It is one thing to seek redress from BP, another to vilify it as an alien invader. He is interested in economics and technology; but not in how you make money. That coolness is a weakness; but it takes a lot more than indifference to destroy America’s spirit of capitalism. Big government and free enterprise have co-existed productively in America since the second world war. Most Americans expect that to continue, and it almost certainly will.

10.KAL's cartoon

9.At last, more transparency in Europe's banks

IT IS buried in article 14 of an uninspiring set of summit conclusions, but the 27 leaders of the European Union took a useful and important decision today, namely to publish the results of stress tests on Europe’s 25 largest banks.

For all their populist attacks on “immorality” of financial markets and vows to rein in “casino capitalism”, their sensible decision-taken at a one day meeting in Brussels-was prompted by market pressure. In short, for all their faults, markets have once again provided the only reliable source of discipline and rigour in this whole euro crisis.

It was the same in February, when EU leaders gathered in Brussels to wag their fingers and vow to stand by countries in the eurozone, in a bid to halt market attacks on Greece. However, their refusal to spell out what they meant meant that within days markets had called their bluff. Four summits later, the EU agreed a ?750 billion eurozone defence mechanism. Markets can and do get things wrong, and rush about in herds. But no other force has been able to make EU politicians sit down and agree what they need to do to save the single currency.

The idea of making public these tests-that measure the ability of banks to survive various horrid economic scenarios-came from Spain. Spanish banking regulators and government officials have been pushing for publishing stress test data for some days, arguing that international markets were taking too gloomy a view of Spanish banks, and that a dose of transparency would act as a positive, calming surprise.

The Germans were more reticent, with the boss of Deutsche Bank, Josef Ackermann, saying last week that he supported publication of stress tests in principle, but that going public would be “very, very dangerous” if mechanisms to support European banks were not in place beforehand. Unsurprisingly, Germany’s public sector banking association, is still opposed: it represents the regionally-owned Landesbanken where many of Germany’s scariest financial skeletons lurk.

The Spanish forced the pace, however. Officials here in Brussels say that only two Spanish banking groups, Santander and BBVA, are big enough to make the 25 covered by the summit conclusions.

But the governor of the Bank of Spain, Miguel Ángel Fernández Ordóñez, a man of good sense who has been at the forefront of pushing for structural reforms (making him few friends in the Spanish government), announced yesterday that stress tests would be published covering all Spanish banks. That includes tests on the troublesome cajas-credit co-operatives that are often controlled by powerful local politicians and which have been resisting pressure from Madrid to merge and restructure. The tests will cover: “not only for what would currently seem to be the most reasonable scenarios, but also for complex growth scenarios in the near future”, he said. If by the end of June, any institutions are still resisting restructuring and recapitalisation by the FROB (Fund for the Orderly Restructuring of the Banking Sector), then the central bank “will act”, said Mr Fernandez Ordóñez. That is no idle threat: the FROB mechanism allows the central bank to take over recalcitrant banks, as happened with the church-run CajaSur the other day.

With luck, markets will reward Spain for this transparency. The prospect that openness will help Spain get ahead of the markets has certainly had a good effect on the Spanish prime minister, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero. He began this crisis by hinting that the dark forces of an Anglo-Saxon conspiracy were picking on Spain to destroy the euro.

Tonight in Brussels, Mr Zapatero was still grumbling about unfounded rumours (and frankly, he has a point), but also arguing: "There is nothing better than transparency to demonstrate solvency.”

The European Commission president, José Manuel Barroso, jumped on the chance offered by the new mood of openness to push for a proper cleaning out of the horrors that still lurk in corners of EU banks. “This should reassure investors by either lifting unfounded suspicion or by dealing with the remaining problems that may exist,” he said.

You will never persuade most European politicians to admit it, but they are finally doing the right thing, and it is down to those hated market forces.

7.A change of prescription --The National Health Service

*Giving patients partial control of the purse strings

Doctors’ winning ways lure patients

Doctors’ winning ways lure patients

EVER since the National Health Service was set up six decades ago in the teeth of opposition by many doctors, professionals have dominated decisions over who receives which treatment, and where. The government is now poised to hand more control to patients in a package of market reforms.

Discover the symptoms of what you suspect might be cancer, say, and you can make an appointment with your choice of family doctor. If he also suspects something serious, he will give you a choice of hospitals in which to be diagnosed and treated. On June 8th Andrew Lansley, the health secretary, announced that he wants to extend choice further, allowing patients to opt for one treatment over another in consultation with a medic (in England, that is; devolved regions are free to do things differently). Such choices must be informed. So he will also publish data on results, infections, waiting times and so on.

Payments will be channelled through general practitioners (GPs). Like primary-care physicians in Denmark and the Netherlands, they have long acted as gatekeepers, controlling access to expensive hospital care through referrals. Mr Lansley’s reforms, which he will present to the NHS Confederation, a group of health-service organisations, on June 24th, will strengthen the role of GPs in deciding where the money is spent.

Many hospital doctors are unhappy, citing the school league tables compiled by newspapers using government data, in which those that take pupils from poor families perform badly. They fear hospitals that treat very ill people might suffer a similar fate. But giving patients greater choice over where they are seen has already increased competition in some places. Recent research by the King’s Fund, a think-tank, found that hospitals solicited GP referrals at the edges of their geographical catchment areas. Choice was not a luxury afforded only to townies: the study found that patients outside city centres were more likely to attend a hospital other than their local one than were urban denizens.

Some 70% of people still go local, but many who roamed further afield did so because of a poor experience closer to home. Patients did not pore over data before deciding, but relied on their own and their friends’ and families’ experiences, as well as their doctors’ advice. The researchers concluded that giving patients more choice helps to keep hospitals focused on what is important to their customers.

That will matter as funding is squeezed. Unlike most other public services, the NHS will be spared real cuts, but increasing demands mean it will have to do more for its money. Last month the Department of Health published a report by McKinsey, a consulting firm, showing that the NHS in England could save between 15% and 22% of current spending over the next three to five years-as much as £20 billion-by measures such as making hospitals operate more efficiently, making drugs cheaper and dropping unnecessary treatments such as tonsillectomy.

And giving patients a say in not only where but how they are treated could help the sick, as well as the bottom line. Glyn Elwyn, a professor of primary care at Cardiff University, observes that well-informed patients tend to be more conservative than doctors. Someone with advanced cancer, say, who is offered expensive, aggressive new chemotherapy that might extend life at the price of lowering its quality often opts instead for palliative care. Greater patient choice might not always increase competition between hospitals, but could yet increase happiness and save money.

ese whispers------China's secret media

*Not believing what they read in the papers, China’s leaders commission their own

IN A country where independent information-gathering is kept in check, what China’s leaders know and how they know it matters hugely. A recently leaked speech by Xia Lin, a senior editor at Xinhua, China’s government-run news agency, suggests that even though press controls have been somewhat loosened in recent years, leaders still rely heavily on secret reports filed by Xinhua journalists. Other evidence indicates this fault-prone system is actually gaining in importance.

In the speech last month Mr Xia revealed that the news agency’s public reports about an eruption of ethnic rioting in the far-western region of Xinjiang last July had played down revenge attacks by Han Chinese against members of the region’s biggest ethnic group, the Uighurs. Mr Xia said it was only after reading a classified “internal reference” report on the reprisals that China’s president, Hu Jintao, cut short an overseas tour. A summary of Mr Xia’s remarks was posted online by one of the audience. Censors removed it and tried to stop it circulating elsewhere.

The summary has not been verified. But filing secret bulletins to the leadership is one of Xinhua’s crucial roles. Many of China’s main newspapers also have classified versions covering news considered too sensitive for public consumption. They do not rely on secret intelligence, but merely report on issues that in most other countries would be the staple of journalism: public complaints; official wrongdoing; bad economic news; and foreign criticism.

In recent years China’s open media-which, thanks to the withdrawal of government subsidies, are now more commercially driven-have also been straying into these once-forbidden realms. But despite the growing assertiveness and reliability of at least a handful of open publications, the secret media have shown no sign of withering away. Some of them have gained a new lease of life-secret-sounding information sells well. China’s rapid adoption of the internet has even provided rich material for a whole new genre of classified reporting. And China’s leaders appear to be lapping it up.

The outbreak of SARS, a deadly lung disease, in 2003 exposed critical weaknesses in the “internal reference”, or neican, system. Xinhua’s first SARS report, for leaders’ eyes only, did not appear until February 9th, by when there had been some 300 cases and five deaths, dating back to November 2002. Only two days later did the leadership release the news and tell the World Health Organisation. China’s secretiveness and dilly-dallying were widely blamed for the spread of SARS.

It was not until April 20th that China’s leaders allowed the press to report the outbreak freely. But even as the number of open reports jumped, so too did Xinhua’s neican coverage. Between April 1st and July 10th, the news agency issued more than 2,700 public SARS-related reports in Chinese. It also filed more than 1,000 secret ones, and over six hours’ worth of classified audio-visual material.

In 2003 the number of comments written by leaders in the margins of Reference Proofs, a secret bulletin on international affairs for very senior officials rose by 88% compared with the year before. Six were by President Hu. Xinhua compiles such statistics assiduously to measure the impact of its work. An even more secret version of the bulletin, Reference Proofs (Supplementary Sheets), published more than three times as many reports as in 2002.

Internet usage in China soared after SARS, which boosted the appeal of virtual encounters and e-commerce. In parallel there was a surge in demand from China’s leaders for rapid updates on what the “netizens” were up to. Xinhua compiles these into another laboriously titled bulletin, Proofs of Domestic Trends (A Digest of Online Public Sentiment). In 2007 the agency’s yearbook reported a 15% growth in the number of such reports and a 50% increase in leaders’ comments on them. It seems unbothered by the paradox: public internet chat is rehashed in top-secret reports, divulging the contents of which could result in a lengthy prison term.

The plethora of information on the internet deemed too sensitive for China’s traditional media has spurred the growth of neican. Last July the Communist Party’s flagship newspaper, the People’s Daily, launched a new weekly journal for senior officials, called Online Public Sentiment: Three Rurals Internal Reference.

The similarity of its title to Xinhua’s far more restricted digest might well be calculated to give the impression that it is offering inside information on the dissatisfaction-plagued “three rurals”, which is the party’s way of referring to peasants, villages and agriculture. A sample edition available online is humdrum, but its aura of secrecy commands a subscription rate two or three times that of a standard (and far more informative) weekly magazine. A Chinese editor familiar with Reform Internal Reference, a secret weekly for low-level officials and academics, says much of its contents could be found online.

Chinese leaders themselves sometimes seem to take neican reports, produced as they are by the party’s own faithful, with a pinch of salt. In a commentary in the People’s Daily in April, China’s prime minister, Wen Jiabao, revealed that leaders sometimes had to sneak out incognito in search of unadulterated information.

The open press, subject as it is to a host of censorship directives, is usually even less reliable. At the party’s five-yearly congress in 2007, Xinhua issued more than twice as many neican reports as it had at the 2002 event. In 2009 a senior provincial official called for efforts to ensure that everyone eligible for Xinhua’s neican did subscribe. There must be no “blank spots”, he said. In the realm of the censored, half-censored content is king.

6.The clock ticks-- Global rebalancing

*American pressure for China to revalue the yuan is reviving. Others are less fussed

LIKE his leggier boss in the White House, Tim Geithner, America’s treasury secretary, is fond of basketball. In April he called a timeout in America’s long campaign for a stronger Chinese exchange rate, postponing a report that might have accused China of currency manipulation. His objective, he said, was to use his talks with China in May and the G20 gatherings in June to make “material progress” on rebalancing the world economy. The last of those meetings, the G20 summit in Toronto, will take place on June 26th and 27th.

In basketball timeouts provide an opportunity to regroup and substitute players. In politics they give new problems a chance to come into play. The Greek sovereign-debt crisis deflected the world’s attention from China’s currency and sank the euro, which meant the yuan has strengthened overall even as it has remained fixed to the dollar. It also unnerved China’s policymakers, who began to fret again about financial instability and a slowdown in the euro area, their second-biggest export market. This was not the time, they concluded, to fiddle with the yuan.

That sits awkwardly with Mr Geithner’s hopes for global rebalancing. In this vision of the future, American saving would rise as overstretched borrowers repaid their debts. American households have indeed pulled back dramatically if you count their reduced outlays on houses and home improvements, argues Jan Hatzius of Goldman Sachs. The combined spending of American households and businesses now falls short of their income by about 6.8% of GDP. In 2006 spending exceeded income by 3.7% of GDP.

This retrenchment was offset, and made possible, by a dramatic fiscal swing in the opposite direction. But America cannot long maintain a budget deficit of almost 9% of GDP. A sustainable recovery would require America to sell more to foreigners, aided by a cheaper dollar. And surplus countries, living well within their means, would have to buy more.

Things went according to script until the end of last year, but have since reversed. America’s trade deficit has widened notably this year, to a 16-month high of $40 billion in April. Europe’s travails suggest the outlook isn’t much better: it will probably be importing less and exporting more, because of fiscal retrenchment and a lower euro, taking market share from American exporters.

America can take some comfort from a narrowing of China’s current-account surplus, from 11% of GDP at its peak in 2007 to 6.1% last year. China’s imports have ballooned this year, thanks to its prodigious stimulus spending and a rise in commodity prices. It even recorded a trade deficit in March. But in the year to May exports increased by almost half, resulting in a trade surplus of about $20 billion for the month, the biggest since October. The fear is that China’s strong imports of machinery, oil and ores in the early months of this year may simply have gone into one end of a production pipeline, out of which are now emerging excessive volumes of steel and heavy-industrial products that it cannot sell at home. As Janet Zhang of GaveKal Dragonomics points out, China’s steel exports in May were 89% higher than their average over the previous four months.

Criticism of China’s currency has resurged almost as quickly as its exports. In international basketball, only the coach can call a timeout. But in America, any of the players can interrupt the game. American policymaking is equally chaotic. Unlike Mr Geithner, many congressmen believe China has already run out of time. Charles Schumer, a Democratic senator, has introduced a bill that would authorise America to slap duties on imports deemed to benefit from an artificially low currency. He plans to seek a vote within a few weeks.

With no parallel bill in the House of Representatives, Mr Schumer’s proposal is a long way from becoming law. But Senate passage could press the administration into taking a firmer line. The government could formally label China a currency manipulator in the delayed report, due in early July; or it could rule in favour of several companies-including three papermakers-that have requested duties on Chinese imports because of the cheap yuan.

Would a stronger yuan really save America’s papermakers and other struggling firms? Between mid-2005 and mid-2009, China’s real trade-weighted exchange rate appreciated by about 5.5% a year. If instead it had risen by 10% a year, as many in America would have liked, China’s exports would have been about 30% lower by mid-2009, according to a study by Shaghil Ahmed of the Federal Reserve.

But in China a drop in exports does not translate straightforwardly into a drop in the trade surplus. China re-exports a lot of what it imports, turning hard drives into iPods and iron ore into steel. So when its foreign sales fall, its overseas purchases drop as well. Alicia García-Herrero of BBVA, a Spanish bank, and Tuuli Koivu of the Bank of Finland find that a 10% appreciation of the trade-weighted yuan reduces imports of components by about 6%.

America hoped that other G20 members, particularly in the developing world, would rally to the cause of revaluing the yuan. In April the president of Brazil’s Central Bank described China’s currency as a “distortion”. His counterpart in India made some milder remarks, but India’s government has remained silent. It is the co-chair of the G20’s working group on rebalancing. As a rare example of a big Asian economy with a current-account deficit, it cherishes its role as honest broker.

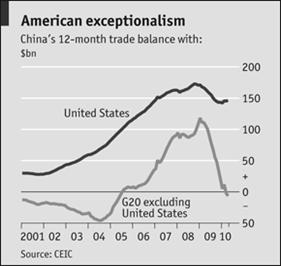

America’s huge trade deficit with China (see chart) sets it apart from many other G20 members. Japan has a surplus of $45.5 billion with China and South Korea $59.1 billion. Even Brazil can boast more than $14 billion. In the past 12 months China has run a trade deficit with the G20 excluding America (even counting the entire European Union as a member).

Getting global imbalances onto the G20’s agenda took some work. China first resisted the idea, fearing the group would put it under too much pressure. But for champions of yuan reform the hope is less that the G20 sides with America against China, more that China feels comfortable enough to use the forum to unveil a policy shift that is in its own long-run interest.

5.Cheques and imbalances --Money from Wall Street

*Financial firms bet on Republicans to fight for their interests

THE recession may have hurt, but re-regulation could hurt almost as much. So in the first quarter of this year the financial services, insurance and property industries spent nearly $125m on lobbying, up more than 11% from last year. The Centre for Public Integrity, a non-partisan research group, reckons the financial-services industries alone hired more than 3,000 lobbyists to influence the financial reform bill now before Congress. On June 14th came news that the Office of Congressional Ethics has launched a probe into the fund-raising activities of eight lawmakers who sit on the House Financial Services or Ways and Means Committees. They are thought to have held fund-raisers days before they voted on financial reform.

The bill has passed both House and Senate, but the two versions still have to be reconciled. Lobbyists hope to water down some of the more contentious provisions, such as a requirement for banks to spin off their derivatives units. They are making their appeals to familiar faces. The senators on the conference committee, which will meld the bills, are some of the biggest recipients of contributions from the financial services, insurance, and property industries, reckons the Centre for Responsive Politics. The 12 senators in question have received over $57m from these sectors during their careers.

If the final bill comes out tough, Wall Street may punish the Democrats. Already, many financial firms have started to spurn Democrats in favour of Republicans. In March 2009 they gave only 37% of their contributions to Republicans. But in March of this year the proportion jumped to 58%. Money-men want to reward Republicans, but they are also betting that Republicans will pick up seats in November’s election, says Jim Thurber, director of the Centre for Congressional and Presidential Studies at American University.

It is not just the reform bill that has prompted financial firms to storm Congress. A provision in the jobs bill, which the House has passed and the Senate is still considering, would hit private-equity shops, property firms and some hedge funds that pay capital-gains rates, rather than income tax, which is higher, on their profits. Congress wants to change this, and has proposed taxing 75% of their profits as income and 25% as capital gains.

On June 8th the Senate Finance Committee threw the industry a bone and proposed that government should tax only 65% of their profits as income. Some cynics note that the third-largest contributor to Max Baucus, the senator who heads the Finance Committee, were, collectively, employees at KKR, a big private-equity firm.

4.I kissed a copyright lawyer

AS THE 1970s were fading into the 1980s and punks were making way for new romantics, EMI-the record company that had brought the world The Beatles-was struggling to keep up with British pop’s ever-changing moods, and got bought up by a humble lightbulb-maker. A cruel joke did the rounds among some employees: “What’s the difference between EMI and the Titanic? At least the Titanic had a couple of decent bands on board when it went down.” Thirty years and various demergers, takeovers, restructurings and buy-outs later, EMI now has some highly successful artists, such as Katy Perry (pictured), Coldplay and Robbie Williams. Financially speaking, however, it is struggling to survive, groaning under a heavy debt burden in an era of file-sharing and iTunes-downloading, in which music fans expect to pay far less than they used to for songs-if anything at all. In recent days EMI’s owner, Terra Firma, a private-equity firm, has had to pump in fresh capital because it had breached its banking covenants. On June 18th it announced drastic management changes and an important strategic shift. Two of its bosses, Charles Allen and John Birt, will leave, and the head of EMI’s music-publishing division, Roger Faxon, will become chief executive of the whole company. EMI also announced that it would “reposition itself as a comprehensive rights-management company serving artists and songwriters worldwide”. Rough translation: owning and exploiting the copyright to songs, rather than selling recordings of songs, is where the money’s going to be from now on. Private-equity firms like Terra Firma have been keen on media companies, even ones in declining industries, because they throw off a lot of cash. Essentially, Terra Firma’s miscalculation with EMI was that it declined much faster than the private-equity firm had expected. However, the music-publishing side has not done anything like as badly as the better known part of the business, that of signing up new singers and bands, and putting out their recordings. EMI’s music-publishing side has remained well-regarded because, under Mr Faxon, it has been so innovative. It has succeeded in getting its songs used in more films, television shows and advertisements, for which handsome royalties are charged. Music publishers have done well out of the boom in music-oriented television shows, from “American Idol” to “Glee”. EMI still faces a considerable struggle to emerge from under its debt mountain and pursue its new business model, but at least it now has a plausible strategy, and a boss who seems to know how to make it work.

3.Turning-point-- The human-genome project

*Ten years after the reading of the human genome, humanity is about to confront its true nature

THE oracle at Delphi had two maxims posted above the entrance to her chamber, for the edification of those who sought her prophecy: “Know thyself” and “Nothing in excess”. Self-knowledge is often the hardest to learn and the least welcome, but the brutal truth is best. Humanity had better hope so, anyway, for the truth will soon out for the entire species.

June 26th marks the tenth anniversary of the reading of the human genome-the 3-billion-letter-long message that promises self-knowledge to humanity. Each letter is a pair of chemical bases that has accumulated over the 3.8 billion years that life has existed on Earth.

Viewed that way-the addition to the message of slightly less than a base-pair a year-the evolution of something as complex as a human being is not such an incredible journey. But it is still an amazing one. Some of it is lost, as the DNA palimpsest has been erased and re-written. Much is the scribbling of vandals who have broken in and scrawled, “We woz ’ere”, in the barbarian tongue of viruses, not yet erased by nature’s librarian, natural selection. And plenty of the rest, the bit that should make sense, can be read but is not yet understood.

But it will be. Humanity’s foibles will be laid bare. The species’s history, from its tentative beginning in north-east Africa to its current imperial dominion, has already been revealed, just through being able to read the genome. It is now possible, too, to compare Homo sapiens with his closest relative-not the living chimpanzee, with whom he parted company perhaps 5m years ago, but the extinct Neanderthal, a true human. That will do what philosophers have dreamed of, but none has yet accomplished: show just what it is that makes Homo sapiens unique. The genome will answer, too, the age-old question of original sin. By showing what is nature, it will reveal what is nurture-and thus just how flexible and perfectible the human animal really is. Ecce Homo

That is not, of course, why the genome project started. The pragmatists who began it were motivated by medical considerations. Diseases would be understood better and new targets for drugs discovered.

This is happening-more slowly than many hoped, but inexorably (see special report). So, too, is the industrialisation of genomic knowledge as better crops and clever ways of using micro-organisms to make chemicals are developed. Indeed, synthetic life itself is within humanity’s grasp, as Craig Venter’s announcement on May 20th of a bacterium with a synthetic genome has shown.

All these are great advances-but in the end, perhaps, not as great as the threat and promise of self-knowledge. Which recalls the oracle’s second admonition: nothing in excess.

Genomics may reveal that humans really are brothers and sisters under the skin. The species is young, so there has been little time for differences to evolve. Politically, that would be good news. It may turn out, however, that some differences both between and within groups are quite marked. If those differences are in sensitive traits like personality or intelligence, real trouble could ensue.

People must be prepared for this possibility, and ready to resist the excesses of racialism, nationalism and eugenics that some are bound to propose in response. That will not be easy. The liberal answer is to respect people as individuals, regardless of the genetic hand that they have been dealt. Genetic knowledge, however awkward, does not change that.

湖北省互联网违法和不良信息举报平台 | 网上有害信息举报专区 | 电信诈骗举报专区 | 涉历史虚无主义有害信息举报专区 | 涉企侵权举报专区

违法和不良信息举报电话:027-86699610 举报邮箱:58377363@163.com